How to read this article - The Drafter Newsletter explores what it means to write in the age of AI. It looks both into the past and into the future; it celebrates the wonder of writing as a human endeavor up until now and the emergence of AI powered ‘writing tools’ of the future. It comes with a strong bias that anything that interferes with human creativity and growth is objectively bad. At the same time, humans are tool users and it explores the mixture of subjectively good or bad uses of AI in the writing process. Today we look at an important precursor to writing which is personal knowledge management and synthesis. The kernel of the article is essentially a brief review of the excellent book ‘How To Take Smart Notes’ by Sonke Ahrens with observations relating to our theme. We consider those gems that are our personal notes earnestly curated as ‘little data’ and we relay a beautiful message - Little data empower Big Writers!

What is little data?

Well firstly, its not big data. Big data is the stuff that is only valuable in the aggregate, when all life and individuality has been sucked out, the stuff that turns us all into datapoints. Little data is not that. The little data I have in mind is also not quite the stuff Nicholas Carr wrote about in his lovely Hedgehog Review article, All the Little Data: Speaking the Langauge of Robots which seems to me to be just Big Data turned inside out, as viewed by us. As he puts it, Little data are all those fleeting, discrete bits of information that swarm around us like gnats on a humid summer evening. Measurements and readings. Forecasts and estimates. Facts and statistics. Yet it’s the little data, at least as much as the big stuff, that shapes our sense of ourselves and the world around us as we click and scroll through our days.

Instead I like to think that little data hold meaning in their specificity. They are unquantifiable and non-aggregable. They are something we all crave right now. Little data find meaning in how they connect to other little data, how they connect to us and our memories and experiences. In a world with too much information I often find myself completely mesmerized by tiny little details, wonderous in their randomness or perhaps in how absolutely common they are, something right under our noses that we never noticed before. Here are some recent encounters -

In the little factoid category (see my note on factoid); That kakorrhaphiophobia is an abnormal, irrational, and persistent fear of failure. It can be so intense that it prevents people from doing anything, even the most minor task; that Komorebi is the Japanese word for sunlight filtering through leaves. Tsundoku is the Japanese word for the stack of books you've purchased but haven't yet read... It is not lost on me that finding fascination with Japanese words is an odd western fettish (see notes).

In the ‘this was right under my nose’ category; The surprising fact that if you somehow find yourself at the bottom of a well you can see the stars even in daylight. Also in this category; As I read in The Shallows, writing when invented did not have word breaks and punctuation. Scribes simply captured as-is the spoken word rolling off the tongue; the same book also observed that it was first considered an odd thing to read to one’s self in one’s head and also that it was the English and Irish monks that introduced punctuation thus making reading easier. Because I myself am Irish this is also a case of connections enriching little data. Once again in the ‘Irish connection’ category; sucking nipples was a means to pledge loyalty to the Kings of pre-Christian Ireland. This one seemed strange to me when I encountered it so I did at least the obligatory Reddit fact check.

Back in the little factoid category but coming to our main theme (this one I foraged when reading Flights); Ropography is the painting term for the attention the artist pays to trifles and details.

Maybe what are trifles and details to us are, for the virtuoso, knit intricately into the fabric of the thing in quite meaningful ways. The little data I have in mind are such entwined trifles.

Little data are often banal in the way something can only be subjectively banal. I am thinking of a first trip to Japan. Flying there on the eleven or twelve hour flight you read your guidebook, preparing yourself. Even still, Tokyo slaps you in the face. Its Big. The neon streets of Shinjuku are big, Shibuya is big, Kyoto seems profoundly spiritual with one of the world’s prettiest streets. Yet I have the strangest feeling on some random street in Tokyo that I shouldn’t even be on. This happens in Tokyo. Its easy to get lost since Tokyo is organized sort of like a fractal from tokubetsu-ku down to chome and the largest skyscrapers sit right next to the smallest buildings. If the footsteps of tourists were a density plot on a map, here on the map there is the little road very few people turn to trod upon, maybe a datapoint or two dotted over time. And off this quotidian road a little side street that no tourist has any reason to go down. What is there? Nothing, just monday morning. A corner store. A delivery man. A small place to eat Gyoza. I have no reason to be there and I feel far from home. Thats why I travel.

Little data is that little street in Tokyo.

Big data is somewhere in the normal distribution’s mass while little data loiters somewhere out in the long tail. Inside the mass of big data, anomalous outliers are washed out. We see this in YouTube’s odd recommendations or ChatGPT’s vapid prose. Little data holds a sort of meaning that big data lacks. Little data are data in context lying in the space between abstract datapoints. They grow slowly with us over time.

I read an article by Doug Clinton - Defining the Future of Human Information Consumption. He starts by observing that we are drowning in information. This is known. He reminds us that its time to reintroduce meaning to information. He attempts to take us from an information age to an experiential age. Here, all meaning is established as a consumer’s interpretation of the creator’s intent. His notably utilitarian perspective considers meaning per units of time - it is not the quantity of information that is important…

… the amount of meaning we derive from a message is now paramount, as is the time it takes to consume the message.

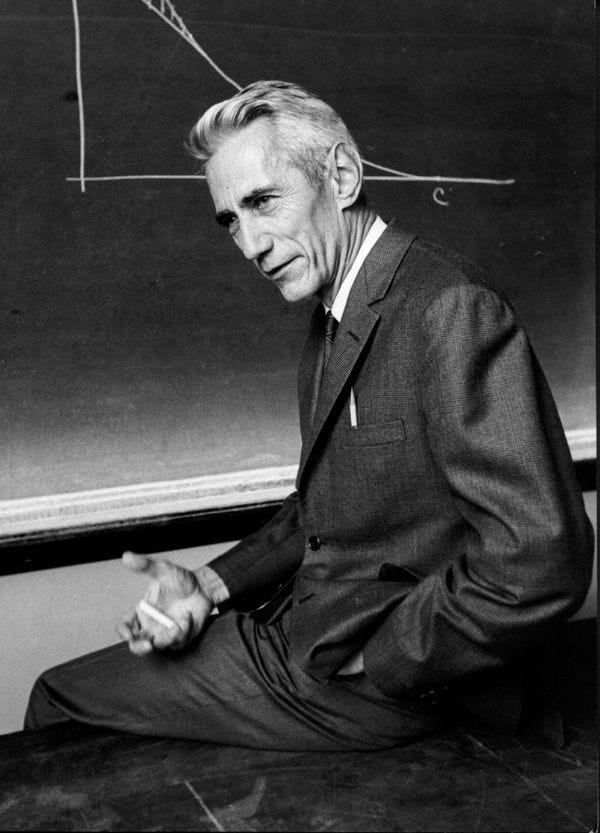

Clinton leans on the classical information theory of Shannon. If the name is not familiar, Shannon is one of computer science’s heroes, the inventor of information theory. You should at least be impressed by how wise he looks in the image below. He reminds me of Gandalf with a chalk instead of a staff.

Doug Clinton gives the example of Gifs (memes) for information compression. These convey meaning quickly and they move through the ecosystem quickly as a result. Not only are these pictures speaking a thousand words but they take advantage of the Zeitgeist, of what is already in the air. These have the quality of little data, morsels of meaning that cannot be excised from context and they thus compress information and meaning. Of course I am more interested in little data for writers than I am memes, but the spirit is similar in this context.

Clinton concludes with a message for industry which I think applies to writers.

Discovering ways to leverage new content formats and technologies in ways to transmit useful information is our future. Demanding more meaning from that information we choose to spend time with is the next evolutionary step for humanity.

In the book How To Take Smart Notes. If you have not yet read it, you may have heard of its subject, Zettelkasten, which translates as slip-box. This is well known in personal knowledge management circles. If you are someone who writes and you have not read this book, I can safely say its one of the most useful books you will ever read. I am not going to try to summarize it here. Its a short book, you can read it in a day or so. I just read it this weekend.

What I did not expect when I picked up the book was how the method originated from one Niklas Luhmann. I make here a little digression because the name has some personal significance to me.

A long time ago, at the very beginning of the current millennium, I was just starting my masters in computer science. My subject was to be distributed systems. But I became fascinated with a question. It was not a question about distributed infrastructure. I became curious about dynamics of information on networks. At the time I did not know how to articulate the question but I felt there was something “strange” that happened on networked systems in the aggregate. I trawled the second floor of the library where computer science books lived. But I could not find the answers I was looking for. In fact, I could not even find the question. In retrospect I probably should have known better because three years earlier, Watts and Strogatz had already published their celebrated paper on networks and a year later Albert Barabási would publish Statistical mechanics of complex networks. So much seems obvious in hindsight but life is lived in the now.

Ignorant, I wondered up to the next floor in the library, to the seemingly forbidden and softer sciences, and found Niklas Luhmann's book on Social Systems. This opened up a new world of ideas for me. I came to appreciate the particular significance of the concept of emergent properties of social systems. Of course this book had nothing to do with distributed systems in computer science but then again, I am not the first person to be thwarted by the lack of Consilience in the sciences. With a new world view, I switched my topic to evolutionary systems and swarm intelligence. From there I stumbled again in confusion, this time into thermodynamics and statistical physics, which eventually led me to do my PhD in statistical field theory ten years later. I trace a direct line from my going upstairs to a forbidden floor of a library, to picking up a book, pulling on a thread and pulling on it some more… to all my research interests ever since.

That is my relationship with Luhmann. A beginning.

Behind his particular personal knowledge synethsis methodology is, implicitly, a beautiful graph theory. What is graph theory? Graphs are similies for nerds. They are not just a way to connect things but a way to find congruent patterns and structures. Congruences in graphs are a little like metaphors - but for nerds.

End of digression.

The book How To Take Smart Notes, promises that those who take smart notes, will never have the problem of a blank screen again - which should appeal to writers on Substack or writers with writing schedules in general. Taking notes is something everyone can do, and maybe everyone thinks they do smartly. The book urges us to look again at the simple idea of taking smart notes. In an information-rich and meaning-poor internet age, its worth paying attention to the thesis of the book. It considers what you can do differently in the weeks, months or even years before you face the blank screen…

to efficiently turn your thoughts and discoveries into convincing written pieces and build up a treasure of smart and interconnected notes along the way.

We, the curators of our own notes, hold a unique perspective of the world. If the community on Substack teaches us anything it is that there is value in the things we perceive and the unique way we perceive them. By keeping smart notes, overtime, they appreciate in value as they mingle with other notes. Luhmann puts it that,

Every note is just an element in the network of references and back references in the system, from which it gains its quality.

What is most striking about the Zettelkasten method is that it treats a system of notes like a living system, a living process. Processes have history. If you and I encounter the same environment, the same internet, the connections you make will be different to mine. One of the fascinating things you learn when you study networks is that they are histories frozen in time. The unique connections we make in our notes and in our minds can turn little trifles into gold. It is indeed a type of alchemy. Some of the most interesting newsletters on substack are those heterogenous ones that span disciplines and form new connections.

In any advice on writing, you are encouraged to trust your perceptions and trust your voice. Take the simple advice in Pity the Reader,

Find a subject you care about and which you in your heart feel others should care about. It is the genuine caring and not your games with language, which will be the most compelling and seductive element in your style.

Klinkenborg in A few Short Sentences About Writing urges us to notice. He says,

Noticing is about letting yourself out into the world, Rather than siphoning the world into you In order to transmute it into words.

He reminds you that if you notice something, its because its important and

Who's going to give you the authority to feel what you notice is important? It will have to be you.

Kant’s call to action in the Enlightenment was sapere aude, dare to know. Klinkenborg seems to say sapere animadverte, dare to notice. The slipbox method allows for the gradual accumulation of the little gems that are our noticings. Read with pen in hand! it urges.

This is a very comforting idea to me. It almost celebrates boredom and idleness to get work done and it certainly celebrates time as an ingredient. Time is always my favourite ingredient. While the slipbox asks us to read less passively, we are in some sense writing more passively because by the time we sit down to write, the work should be almost done. When we are reading, we are making notes. When we are making notes, we are forming connections. From all these connections the first draft emerges. From there begins the phase we normally think of as actually writing.

By the way, I currently do not have a good slipbox workflow. So this article has been far harder to write than it needed to be!

We collect ephemera as we go through our (digital) lives. These have value to our writing. I think of this like approaching cooking in one of two ways. In scenario A we make a plan, we look up a recipe and write down ingredients. We go to the supermarket with our list. We pick things up, cross them off our list. We return home and make the thing, according to plan. In scenario B, we have no immediate plan to cook. We amble around on a sunday morning in the farmers market or the local deli. We pick up this or that from time to time. We take it home and put it in the pantry. We do this over time. On another day maybe we decide to create something from whatever happens to be in our pantry. Maybe there is a spectrum from A to B. Somehow I like the idea of the foraging lifestyle of our hunter-gatherer ancestors but after they learned to cure and preserve. Some writers argue they were freer and healthier than we are now. I simply like the thought of living the life of a hunter-gather with a slip-box. That may well be what we in Ireland call a figeary.

The slip box is at odds with conventional planning and the top down structuring that atomizes knowledge. Instead we find it celebrating connectivity. Ahrens says, Most people try to reduce complexity by separating what they have into smaller stacks, piles or separate folders. They sort their notes by topics and sub-topics, which makes it look less complex, but quickly becomes very complicated… it reduces the likelihood of building and finding surprising connections between the notes themselves.

On our central theme of writing in the age of AI, while I think AI should be kept away from generative writing, it seems likely that personal knowledge management and synthesis will be one of the killer apps in the coming years. Michael Spencer and Alex McFarland have written a nice article on Google’s Notebook ML and talk about how this can be integrated into a researcher’s workflow to good effect. Behind these types of systems, the most relevant technology is probably graph-enhanced RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation). I did say graph theory is just similes for nerds but writers do benefit from a personal knowledge graph. I believe that is where little data lives and breathes, and breeds. Combined with the philosophy of Zettelkasten this turns us each into alchemists. I believe it is in this way little data can empower big writers. This is a significant part of what I think good writing tools look like.

Notes

[A] Speaking to ChatGPT

I asked GPT for a word that describes fascination with Japanese words that capture an idea. Its first suggestion was too literal so I asked for something more archaic or poetic…

GPT: For a more archaic or poetic approach, we could craft something inspired by classical Japanese linguistic aesthetics. Here's an attempt:

言趣狩り (Gonshu-gari)

言 (gon): An old reading for "word" or "language."

趣 (shu): Essence, flavor, or charm.

狩り (gari): Hunting, as in cherry blossom viewing (花見狩り, hanami-gari).

Together, this could mean "hunting for the charm of words" or "chasing the essence of language." It conveys a slightly whimsical sense of seeking out the unique beauty in another language.

異趣見 (Ishu-ken)

異 (i): Other, foreign, or different.

趣 (shu): Essence or flavor.

見 (ken): To see, observe, or notice.

This suggests "observing the charm of the other," capturing a fascination with pointing out interesting aspects of another culture's language, perhaps even with a tinge of playful self-awareness.

[B] On the word factoid and factoid autopsia

The word has two meanings, according to Merriam Webster - one is the sense coined by Norman Mailer about something given as fact (that may not be true) after appearing in the medium of magazine. The other usage is a piece of trivia that may be true. My usage sits somewhere in the middle. Each such factoid should be checked by ourselves. These are interesting, in any case, as real experience of discovery; Klinkenborg discusses the word autopsia - or to see for one’s self.